Interview with Lou Harrison, 1987 by David B. Doty is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Interview with Lou Harrison

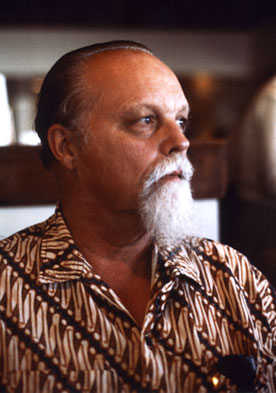

I conducted this interview with just intonation and world music pioneer Lou Harrison at Lou and Bill Colvig’s home in Aptos, California, in February 1987; it was originally published in 1/1, the Journal of the Just Intonation Network, issue 3:2, Spring 1987. I remember that Lou and I were both recovering from bad colds and hacked and coughed our way through many hours of conversation.

Lou Harrison (1917–2003)

DD—I have heard, of course, that hearing Chinese opera in your youth in San Francisco was some kind of fundamental stimulus in your career. Were you conscious of the fact that that music involved a different tuning system, at that time?

LH—No, I don't think I was, because I didn't know about different tunings. I was charmed and excited by the operatic nature of it, and the complete difference from European opera. It was comfortable, for one thing. You didn't have to get dressed up in fancy clothes and be afraid you'd touch your neighbors. By the time I was 21, I think I'd only heard two Western operas, but I'd heard many, many, many Chinese ones. Because at that time in San Francisco, when I was going to San Francisco State, you could walk in off the street in Chinatown, and for a quarter you could spend the whole evening. There were tables, and you learned about dried plums and sunflower seeds, and things like that, which the general Anglo Saxon population hadn't yet encountered as health food. It was Cantonese opera, which meant that it was one beautiful aria after the other, it not being, how shall I put it, as crisp or detailed or sharp as Peking opera.

…At the same time in San Francisco, during my adolescence, there were beginning to be printings of Colin McPhee articles, in Musical Quarterly, for example; and I was studying with Henry Cowell about this time, and through his courses, I heard examples of the Hornbostle collection in Berlin, where he had studied in the early '30s. And I heard Balinese gamelan for the first time—you're so young, I don't know if you remember, do you remember back as far as Treasure island?

DD—No, that was before my time.

LH—Sorry about that, because it was wonderful, it was a beautiful place. The goddess Pacifica presided over it. At any rate, it was a very beautiful fair, and there I heard live gamelan over the water. There was a lake where the Indonesian Pavilion was—by the way, that would not, it occurs to me, since it was in the '30s, it would not have been Indonesian, that would have been Dutch East Indies, wouldn't it?

DD—I guess so.

LH—Funny, still think of it as Indonesia, because now I’m so strongly attached to Indonesia as such. At any rate, the gamelan played, and I heard it live for the first time. And at the same time, at the Curran Theatre in San Francisco, there was a Javanese dancer, and that was the first time I’d ever seen the very slow and exquisite evolutions of Javanese dance. Not Balinese, which is, as you know, very peppy and hyped up, but the Javanese style. I marveled then at how anyone could move so slowly and gracefully, and contains so much quietude, so to speak. And so, those were the stimuli from the orient.

DD—When did you first become interested in Just Intonation?

LH—When Virgil [Thomson] first got a copy of Harry Partch's book [Genesis of a Music], he gave it to me, and said, "See what you can make of this." That was my conversion, so to speak. From there on, I’ve consistently worked in tuning as a part of my real life. It came at just the right time, David, because for years I was doing things like writing a completely white-note piece. And then I’d write another piece in which I’d allow myself one accidental, and then another piece in which I’d allow myself two accidentals, and so on 'till finally I’d do a row piece. Then the whole thing would start allover again. Then I realized that to do a twelve-tone piece was the same thing as to do a white-note piece. It was a squirrel’s cage: 'round and 'round and 'round the cycle. And when the Partch book hit me, and I realized that you could have real intervals, then, of course, everything changed immediately. The problem has never arisen since. Because suddenly everything makes sense, and the intervals are real. You have a reason for the musicality. So, from then on, that would have been 1948, I think the book came out in 1947…

DD—That sounds about right.

LH—So when I came back west, after that brief period in Black Mountain College, I got acquainted with Harry, and from then on until his death we were good friends. The minute I came back to California I—I had already started, though, in New York, on the simplicity and tonal tack, and this was, in part, due to the Partch book. I wrote, in 1954 here, as a commission from the Louisville Orchestra, I wrote my "Strict Songs," [Four Strict Songs for Eight Baritones and Orchestra, Louisville Orchestra—First Edition Records, Lou-58-2] which is a prototypical minimalist piece. I originally designed it to exist only in one octave, but then I orchestrated it, you see. And this is also in Just Intonation for an orchestra. And John Cage, when I told him about writing it in just one octave, he said, "Why that's the mass of the straight and narrow path." And that's the first thing I wrote when I got out here. Then I started working with Asian instruments, and so it's gone ever since.

So I continue. I apparently laid out my toys on a fairly large acreage when I was quite. young. By the time was about twelve or thirteen, I had already carved a small violin, and altered the family phonograph to give it a bigger horn. The gamelan world has been an absorption for the last ten years, at any rate. That's, of course, due to Pak Chokro [K.R.T. Wasitodipuro, Javanese master musician and composer, and leading teacher of the central Javanese tradition—Ed.]. I don't think I’d ever have written for gamelan if it hadn't been that Pak Chokro directly asked me to. Because I had in mind the notion that all the Javanese gamelan at any rate, were all busy playing, academically, classical Javanese music, under classical Javanese musicians, and as an American, you didn’t have access to it. That's why you built one, I’m sure.

DD—Yes.